Preface 2023

Preface – magazine 2023 A contemporary magazine feeds upon dynamism and vigour. It instantly perceives the inputs deriving from the readers and evolves, offering its best at...

Filter by Category

Preface – magazine 2023 A contemporary magazine feeds upon dynamism and vigour. It instantly perceives the inputs deriving from the readers and evolves, offering its best at...

The Westernization of Japan: the Meiji Renewal With the expression Meiji Renewal (明治 維新), we indicate the radical change in the political, economic and social structure of Japan,...

4A Liceo scientifico (astronomico) – Gobetti-Volta, Bagno a Ripoli (Firenze)* The universe that revolves around food and Renaissance banquets has always had a link with the...

During the classic lunch breaks at the office, dinners with friends or Sunday brunches, how many times do we happen to think about the technology associated with the meal we are...

The subtleties of nature and health One of the most significant female figures of the early Middle Ages, Hildegard, lived along the Rhine River, in the tract that separates Hesse...

“Autumn. We already heard it coming / in the August wind, / in the September rains / torrential and weeping…”, this is how Vincenzo Cardarelli sang this...

“Let him bring huge lampreys or enormous salmons or pike, without letting it be known. A good eel is hardly bad, shad or tench or some good sturgeon, cakes or stuffed...

The use of national cuisine and typical local products has always been a powerful tool of cultural diplomacy to improve the country’s image and increase its influence and...

“He possessed great talent at painting flowers and figures”. It seems an obvious statement for our times, but the famous phrase, attributed to Caravaggio, overturned...

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food....

We have spent the quarantine with our hands in the dough and we know more about yeast and flour. We now want to take a small trip to discover the “good smell” in...

With the expression Meiji Renewal (明治 維新), we indicate the radical change in the political, economic and social structure of Japan, which marked the end of the secular Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial authority, in the person of the Meiji Emperor (明治天皇) between 1866 and 1869.

We find the origin of this decisive turning point in Japanese history with the so-called Black Ships incident. This crisis has long marked the historical memory of the country as the symbol of Western imperialism.

It showed the technology advancement of Europe and the USA over to Japan. In the summer of 1853, under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry, a fleet of four US warships (defined black for the colour of the smoke produced by coal engines) anchored in Tokyo Bay. It forced the government of the Shōgun to open Japanese ports to foreign trade, disclosing the century-long international isolation of land of the Rising Sun – except for the Netherlands and Qing China, allowed to trade just at the Nagasaki port.

Since then, the interference of Western powers into internal politics has grown even more. It caused a crisis, now latent in Japanese society, to break out, unmasking the contradictions of a political and socio-economic system that could not match the aggressive and dynamic Western model.

The political forces – mainly made up of those clans historically banned from the power system of the shogunate – opposed to foreign interference and consequently gathered around the figure of the Emperor and started the Boshin War in 1868 (戊辰 戦 争, “the war of the Year of the Dragon”) against the government of the Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu.

Their victory in the civil conflict brought about the dismantling of the Japanese feudal system and the ensuing foundation of a massive and impressive modernization of Japan, to get on a par with the European West.

The end of the Tokugawa shogunate coincided with the advent of a new ruling class. An oligarchy, composed by members of the imperial court and the great feudal lords who favoured a change, promoted a radical reform process inspired by the Western models they feared and fought but deeply admired, too.

They aimed at the emancipation of Japan from Western powers. Besides, in the second half of the nineteenth-century, modernization was equivalent to westernization. Favoured by the ruling leaders, and not the people, this process involved even the cuisine and eating habits. A slow but profound change arose in the gastronomic traditions of all Japanese society.

The innovation of the country affected almost every sphere of the inaccessible and conservative Japanese society. It influenced its gastronomic and culinary habits, the order of meal courses according to Western etiquette and behaviour at the table.

It was linked directly to the brand-new place occupied by Japan in international relations. The foreign policy of the Meiji Period (明治 時代) government was opposite to that pursued during the shogunate. Instead of universal isolation, the Empire of the Rising Sun aspired to recognition as an eminent Asian power within the Eurocentric international system. To achieve this objective and be part of the great powers circle on an equal footing, it became necessary to convey abroad the image of Japan as a civilized country.

On November 4, 1871, to celebrate the nineteenth birthday of Emperor Meiji, Japanese authorities held the first European-style dinner party in Tokyo, specially set up to entertain Western diplomats.

However, we should stress that they introduced Western-style gatherings to impress foreign dignitaries with their capacity to become “civilized”, and strengthen the new political leadership authority inside Japanese society.

Under the power that, at the time, the Western model carried, cultural conformity to Western standards was, for the Japanese aristocracy and the members of the new government, a way to acquire greater prestige and authority at the internal level.

It explains why, already in the summer of 1871, months before the Emperor’s birthday party, typical European cuisine dishes began to be served at court. They ate according to the etiquette of the Old Continent, even if no Western official was present.

In the Meiji period, the elite adoption of Western gastronomy went far beyond the objectives designated. This process has progressively led to the birth of a hybrid cuisine that mixes Japanese flavours and procedures with European ones, and which still permeates much of the culinary culture of the land of the Rising Sun.

The term yoshoku (洋 食, Western cuisine) indicates dishes imported from the West and adapted to local tastes.

The result is often much different from the original versions. Many decades passed before rural environments, and the lower strata of the urban population, accepted the Western culinary style, albeit blended.

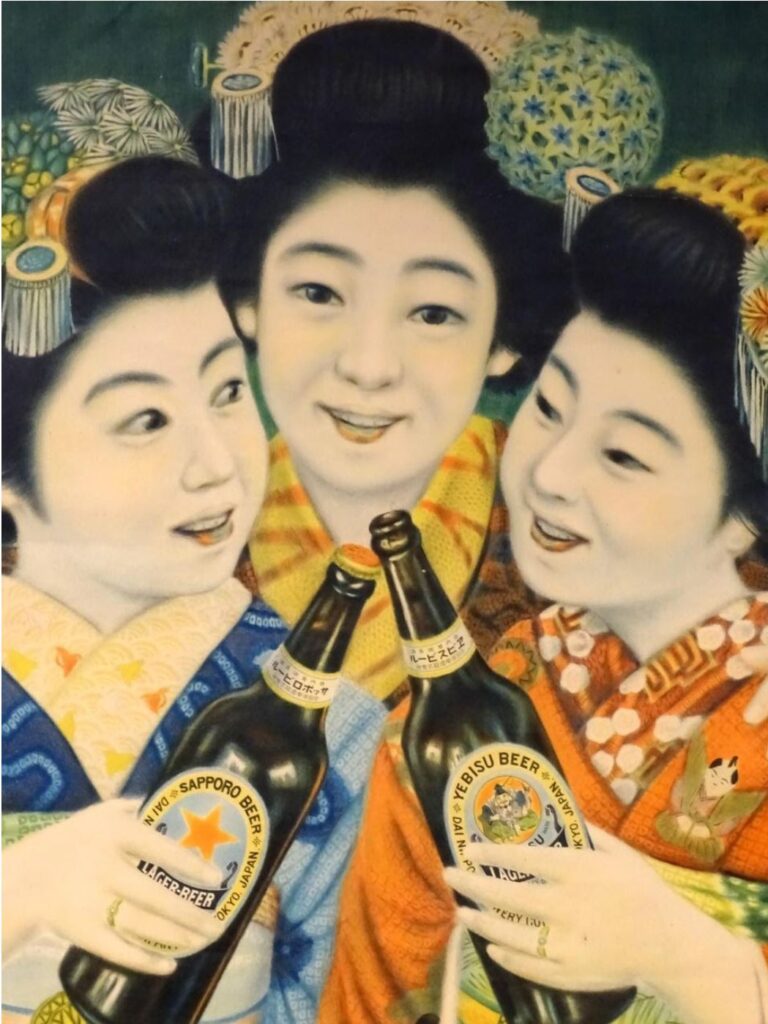

However, the civilized Western flavours exercised incredible fascination on the elite and cultured circles of Japanese society. Even if always looked upon – with a mix of hate and love – by the lower social classes, the latter saw the elite as a model of behaviour and inspiration, and significantly helped the rapid spread of certain types of Western food and beverages, such as beer and biscuits, to major urban areas.

The Japanese middle class, and even those urban workers, were attracted to the Western culinary style because, during the Meiji Period, it had become a distinctive feature of the affluent classes. Finally, we can explain the diffusion and knowledge of Western tastes inside all social strata of urban Japan, in the mid-nineteenth century, as the lower class attempt to imitate the ruling class habits.

The political elite became the propagators of a new gastronomic fashion, Westernising customs and traditions. At the same time, Japan was evolving into a modern state.

The nation-states in the European continent based much of their legitimacy in the defence and exaltation of a unique national culture opposed to other national identities.

In countries of recent unification such as Italy and Germany, the ruling class could rely on a pre-existing common belonging to build a strong nation-state. However, in Japan, at the beginning of the Meiji period, the concept of nationality was utterly unknown. Customs and traditions were much different from an area to another. The idea of the clan was at the basis of the social relations of the Japanese archipelago.

Therefore, the new ruling class had to develop a strategy to introduce an official state culture from scratch, drawn from western political and philosophical models, alien to Japanese culture. In this context, under its ascendancy towards its subjects, the imperial court played a central role in establishing the Japanese nation-state.

Elevated to the symbol of the Japanese nation, the westernization of the Emperor became one of the main tools for the state to mould the masses into modern subjects/citizens, united under his enlightened leadership.

They used every aspect of Emperor Meiji’s life to flaunt change of Japan towards modernity, at that time associated with the West. In 1872, a dovetail uniform held by hooks and ribbons replaced the traditional robes of the monarch, becoming its signature costume, while, the following year, the head of state would cut his hair and grow a beard and moustache.

From a gastronomic perspective, one of the most controversial foods in Japanese culinary history played a fundamental role in this rapid and profound process: meat.

In January 1872, the Japanese government announced officially that the Meiji Emperor had begun to eat beef and mutton regularly. It broke a centuries-old food taboo that since the 7th century AD had banned eating meat or, at least, tried to discourage its presence in the daily diet of the Japanese people.

While there are still numerous cultures that prohibit the consumption of beef or pork for religious reasons, the Japanese social taboo against the consumption of all types of livestock is almost unique and explained, in part, by the respect for the principles of Buddhism, the prevailing philosophy in the Japanese archipelago. It seems that the culture of cattle breeding and meat consumption, which in ancient times developed in the heart of Eurasia and later spread east and west to other emerged lands, had never really reached the islands of Japan. Nevertheless, it had stopped on the Korean peninsula.

The abundance of marine resources has instead encouraged the development of thriving aquaculture, centred on the cultivation of molluscs, crustaceans, fish and aquatic plants such as algae.

Anyhow, we can measure the success of meat in cuisine culture by how they cook animal meats. According to this rule, it is clear that the Japanese are not, even today, true meat-eaters. We can consider the Japanese people the messengers of a cuisine culture based on fish, since they traditionally eat every part of the fish, from the head to the intestine.

In this context, they advanced religious motives: one of the central teachings of the Buddhist religion – very influential in various periods of Japanese history – is, in fact, ahimsa (non-violence towards all living beings), followed by prohibitions to hunt, vivisect and eat animals and to encourage vegetarianism in the faithful community.

The first official ban on meat consumption in the country known to us dates back to 675 AD when Emperor Tenmu (天 武天皇) prohibited the consumption of beef, horse, dog, chicken and monkey meat at least from April to September.

In the following centuries, they extended and reinstated this prohibition several times: the least one dates back to 1687, under the Tokugawa shogunate, which endured until the Meiji Era. Yet, despite the indictment by the new government, meat taboo remained ingrained deeply and not forgotten. In reality, meat consumption in the country would remain relatively low for about another century.

Yet, in 1872, the announcement of the Meiji Emperor new diet contributed to the change in the Japanese perception of meat. It favoured the spread of consumption throughout the archipelago.

Today, we consider Wagyū (和 牛) meat – very famous is that of the Kobe beef (神 戸 ビ ー フ), raised in Hyōgo Prefecture – one of the best and most exclusive in the world, thanks to its great flavour and extreme tenderness.

It is no coincidence that a traditional Japanese saying states that “a steak is perfect if you can cut it with chopsticks”.

Japan embracing Western cuisine represents the typical case of a change in the national gastronomic culture directed by the ruling power.

s we have seen, this was part of a larger and deeper modernization process of the Empire of the Rising Sun following the example of the then successful Western model.

Thanks to this decision, the Japanese archipelago brilliantly avoided the fate of becoming a colony or a depowered entity, as China and the African continent during the nineteenth century.

On the contrary, its ability to adapt to the standards of the major Western countries, selecting the best, combined with an internal policy aimed at concentrating the power around the imperial court, meant that the country quickly became an Asian imperialist power, with an efficient political system and a strong economy.

Japan did not have, therefore, a spontaneous and bottom-up modernization as in the case of the United Kingdom or other European countries, but planned and imposed by the new central government, eager to bridge the gap with the great European powers and become the hegemonic country in the Far East through the adoption of foreign political, economic and social paradigms.

Inside a rapid change promoted at the state level, the Japanese culinary tradition has nevertheless managed to survive, to the point that today Japanese and Western elements coexist together in the modern gastronomy of the Land of the Rising Sun.

LUCA GALANTINI