The taste of words: a history of the Italian of food

Foreword by Giovanna Frosini Materials, shapes, colours, flavours: the language of food transforms all this into words, it coats with sounds a fundamental and daily experience,...

Filter by Category

Filter by Author

Foreword by Giovanna Frosini

Materials, shapes, colours, flavours: the language of food transforms all this into words, it coats with sounds a fundamental and daily experience, which is a vehicle of personal and collective identity, memory and innovation. Following the thread of words, studying the forming of the recipe and the cookbook means that we become aware of this identity, and that we reflect on the unique character of the Italian experience, which comes from the mobile composing of a multifaceted mosaic of many traditions present on the peninsula, always in the name of plurality, confrontation, exchange.

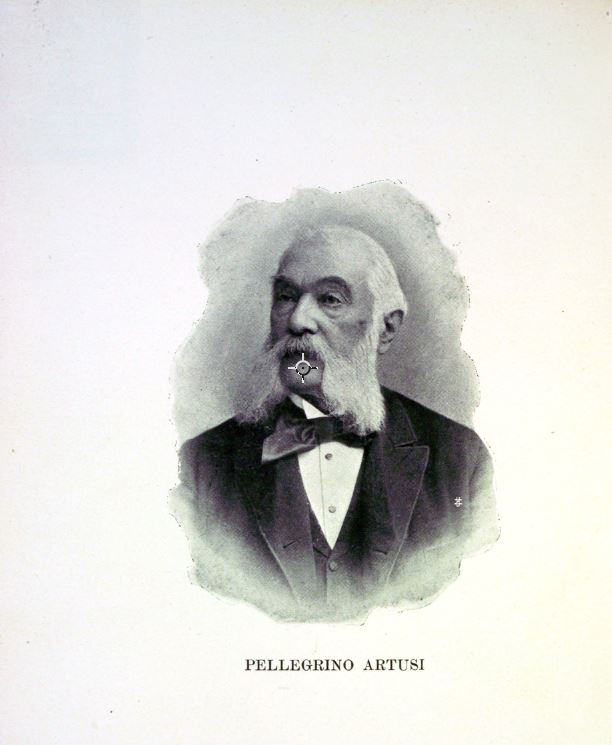

The marvellous journey of the Italian of food unfolds from the distant times of the Middle Ages – with unsuspected continuity of names and preparations, and at the same time profound and radical differences – and reaches us through centuries of great changes, and true turning points. Such is the eighteenth-century passage to the modern cuisine or the ‘pen and pots’ revolution of Pellegrino Artusi who founded the very idea of the domestic cooking for a new society.

Today the Italian vocabulary of food, enriched by many dialecticisms, and even mixed with many foreignisms, seems projected with force outside our country: often with banalization and misrepresentations (if not with real fabrications), but also with the determination and the courage of those who want to preserve a great tradition and renew it in the name of intelligence and creativity.

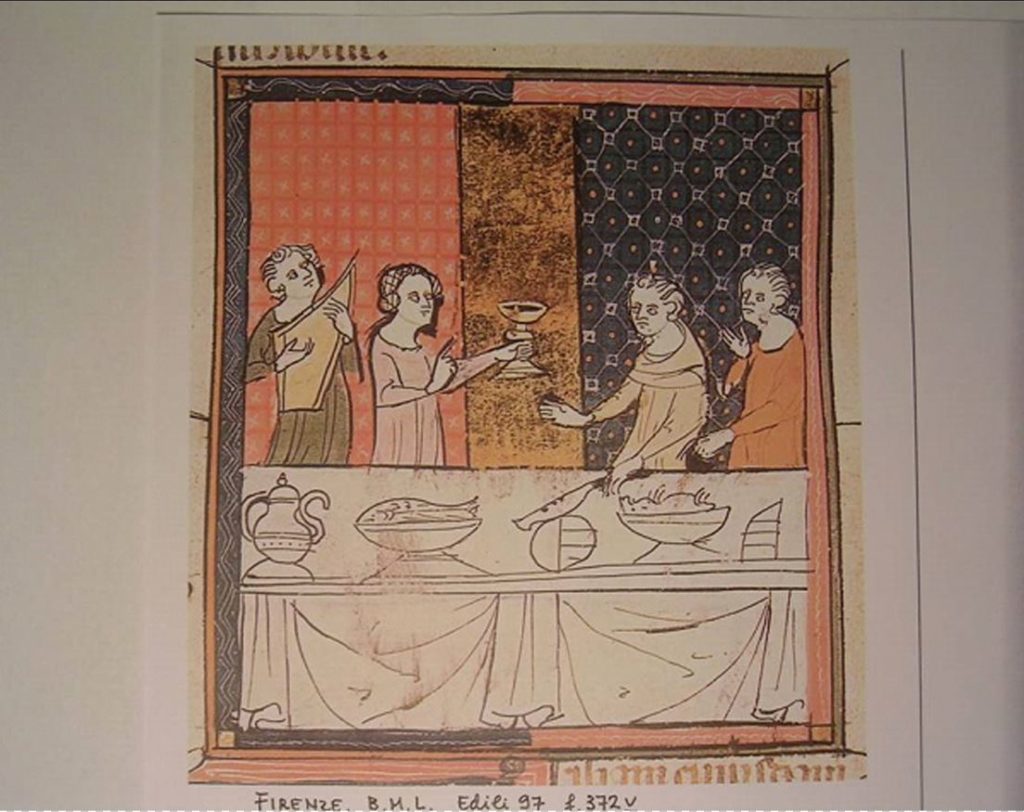

Between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

The Italian culinary tradition is made up of a great variety and it somehow reflects the fragmented political situation that has characterized our country for centuries. We can even consider the language of food as a mirror of this extraordinary variety, where it is possible to identify the strong influence of both dialects and foreign languages.

We can trace the first written medieval records containing culinary terms and cooking practices in anonymous cookbooks, but also inside expense books and diaries. Explicit references to food and information on cooking are present in fundamental works of literary tradition such as Dante’s Comedy and Boccaccio’s Decameron (think of the abundance in the country of Bengodi in the novel of Calandrino and the heliotrope). Dating back to the Middle Ages are words such as pappardelle 1 , cacio parmiggiano, pane impepato 2 (connected to Christmas), mostarda in the sense of ‘sauce made from mustard and vinegar’, vermicelli for ‘the type of threadlike pasta’.

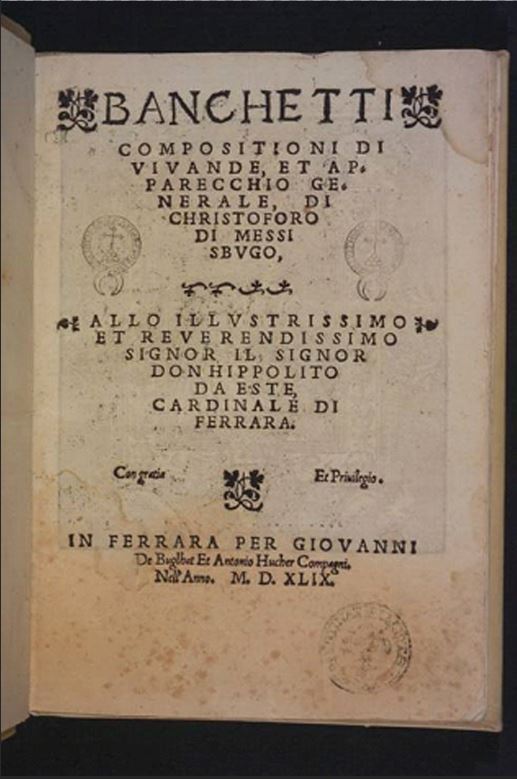

In the Renaissance, the practice of cooking turns into a refined art: the way of conceiving the courteous banquet changes becoming an opportunity to display power and wealth. The work Banquets, Composition of Dishes and General Presentation by Cristoforo Messi Sbugo (Ferrara, 1549) is the most important of the century and becomes a model of gastronomic treatises. Thanks to Banquets, structures such as ‘alla + adjective’ (in the style of – for example the Turkish style) spread, the use of suffixes in -ata 3 (as perata 4 and sfogliata 5 ), words such as torrone (nougat) and crescentine (‘sfogliatine dolci’ – sweet puff pastries).

From the great treaties of the eighteenth century to Pellegrino Artusi’s reform

In the eighteenth century, the great influence of transalpine cuisine and language caused a profound change in the tastes and practices of cooking, as well as a significant loan of French words in the culinary jargon: vol-au-vent, soufflé, and brioche. These are just some of the Gallicisms that still survive in the language of food today, a tangible sign of the great cultural prestige that French civilization had achieved, even in cuisine. Further proof is the Modern Apicius by Francesco Leonardi, the most important treatise of the century.

Written in a deliberately technical language, divided into six volumes, the work represents a veritable encyclopaedia of the culinary art, in which adaptations from the French appear in very high numbers (for example ragù, besciamella, sciarlotta 6 ).

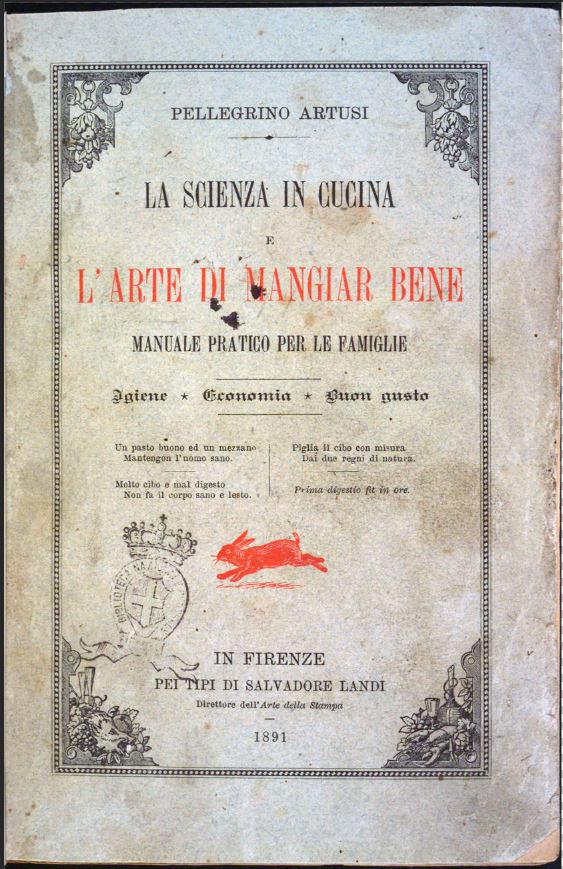

An unclear mixture of dialectal and foreign terms, literary terms and technicalities will be the style of almost all following cookbooks, up to the turning point marked by Pellegrino Artusi’s Science in the kitchen and the art of eating well. Not a book for professional chefs’ use only, but a “practical manual for families” (as the subtitle of the work states). A real novelty, both in content and in the language. After the first edition of 1891, Science in the kitchen will reach a resounding success, gradually enriched with new recipes until the fourteenth edition of 1910, the last edited by the author.

Born in Romagna, a merchant by profession, but a man of great culture, Artusi was the first to grasp the need for a rationalization of the language of food: he adopted the language of Florence for his book. Through this renewed “rinsing of the language in Arno”, he ultimately gives to all Italians a concrete remedy for that incomprehensible language.

An extraordinary variety: the language of food today

A great variety characterizes today’s gastronomic Italian. This originates from historical, social and cultural factors, which during the twentieth century gave life to a language partly unlike the model developed by Artusi. An extraordinary wealth of dialecticisms (such as grissino 7 and fontina 8 , of Piedmontese origin, risotto and panettone 9 , of Lombard origin, pesto from the Genoese dialect, piadina 10 from the Emilian one and so on). Of geography synonyms (different words, used in different areas of Italy, which indicate the same food: for example, think about the great variety of the carnival sweets names), as well as numerous foreignisms from all over the world.

The phenomenon of Italianisms, instead, gives the idea of the prestige and international success of the Italian gastronomy foods: there is a solid background of gastronomic Italianisms, some of which have entered foreign languages since a long time (such as lasagne, documented in the French language from the 16th century). However, most of them become widely known in the twentieth century, especially in the last decades (for example bruschetta, carpaccio, and tiramisu).

Among the historical Italianisms, of course, we find the case of pizza, documented in foreign vocabularies from the nineteenth century but perceived in Italy as dialect still at the beginning of the century (Panzini’s Modern Dictionary in 1905 defines it as “the common name of a very popular Neapolitan food»).A comparison between past and present, among cookbooks, cooking blogs and television programmes, highlights remarkable cases of continuity (as an arista 11 , a word documented since the thirteenth century) and innovations in modern lexical usages (for example, plating up and to plate and the mishmash word apericena 12 ) to show the great richness of the Italian of food.

Essential bibliography

Alba M., 2018, Parole per tutti i gusti. Osservazioni sul lessico gastronomico dei ricettari di Amalia Moretti Foggia, in «Studi di lessicografia italiana», XXXV, pp. 245-88.

Alba M., Frosini G., 2019, «Domestici scrittori». Corrispondenza di Marietta Sabatini, Francesco Ruffilli e altri con Pellegrino Artusi, Sesto Fiorentino, Apice Libri.

Frosini G., 2009, L’italiano in tavola, in Trifone P. (a cura di), Lingua e identità. Una storia sociale dell’italiano, Nuova edizione, Roma, Carocci, pp. 79-103.

2012, La cucina degli italiani, tradizione e lingua dall’Italia al mondo, in Mattarucco G. (a cura di), Italia per il mondo, banca, commerci, cultura, arti, tradizioni, Firenze, Accademia della Crusca, pp. 85-107.

2015, La lingua delle ricette, in Dammi la tua ricetta, Atti del convegno artusiano (Forlimpopoli, 20 giugno 2015 – Casa Artusi). LINK: http://www.pellegrinoartusi.it.

Frosini G., Montanari M. (a cura di) 2012, Il secolo artusiano, Atti del Convegno di Firenze-Forlimpopoli, 30 marzo-2 aprile 2011, Firenze, Accademia della Crusca.

Lubello S., 2010, Lingua della gastronomia, in Enciclopedia dell’italiano, Roma, Treccani. LINK:http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/lingua-della-gastronomia.

Robustelli C., Frosini G. (a cura di) 2009, Storia della lingua e storia della cucina: parola e cibo. Due linguaggi per la storia della società italiana. Atti del VI Convegno ASLI, Associazione per la storia della lingua italiana (Modena, 20-22 settembre 2007), Firenze, Cesati.Vivit: Vivi italiano. Il portale dell’italiano nel mondo. LINK: http://www.viv-it.org/categorie/area/società-e-costume/cucina.

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food....

They showed the film Spartacus, directed by Stanley Kubrick, for the first time in October 1960, in New York. The protagonist, Kirk Douglas, was the rebel gladiator. He was also...