CULINARY RAPSODY: FROM THE FIRST PARTY IN HISTORY TO HAUTE CUISINE

Dear Readers, You will surely know that to embark on this magazine means to venture the thousands of meanings that food and its preparation had and continue to have in the history...

Filter by Category

Filter by Author

Dear Readers,

You will surely know that to embark on this magazine means to venture the thousands of meanings that food and its preparation had and continue to have in the history and culture of different peoples.

The first meaning we usually give to food in relation to human evolution is that of constantly being an important factor in designing and acknowledging the variety of human relationships. Thus, its power to bring people together around a table or any other similar space and hence the way the guests share this space can become the source of sociological and cultural investigation. In addition, the diet of a specific historical period or place can give us reliable information on the average life expectancy of people, on the most commonly spread diseases, and even on the psychological component that a population would have nourished through such distinct diet.

However, the banquet and the stay together, the food and the kitchen vocation all remain the same. There are anthropological reasons of course, but although such reasons are not fully known yet, they remain amazingly human.

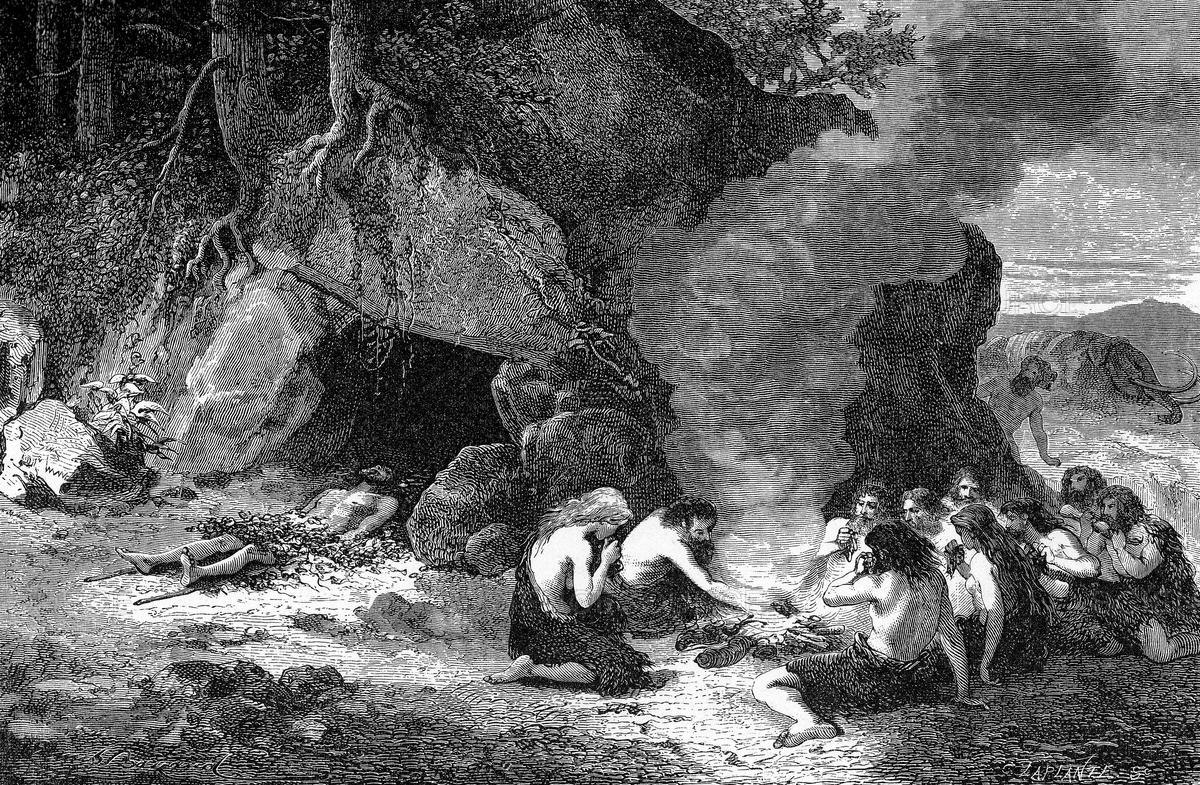

For example, the remains discovered a few years ago inside a Galilean cave, two hundred meters above sea level, demonstrate what we have just stated. The excavation campaign in the cave – which, by the way, has a magnificent view – lasted several years and has unearthed the leftovers of what has been defined as the first party in history. This party occurred about twelve thousand years ago. An accurate reconstruction could establish that the guests were no less than thirty and that the menu had been prepared earlier in advance. They found the remains of three specimens of aurochs, huge bovines now extinct, and of at least seventy turtles.

This conspicuous supply of food had certainly occupied men in days and days of hunting, not without any danger, and in many, many gatherings dedicated to the preparation of such meats. The picture we can envision is that of a population that is no longer nomadic but settled and consequently beginning to join agriculture with hunting. Furthermore, we can see in the now obvious hypothesis that the menu had been prepared in advance the fact that even at that time food and eating together took on a fundamental social and cultural meaning, which went beyond the primary function of nutrition, assuming a symbolic and distinctive content.

Such distant ancestors of ours, in essence, would have consciously started a series of events that would lead to the preparation and consumption of a collective meal, the first party in history. Yet, if this were the case, our friends would not only deliberately create motives in anticipation of events, but in the end, without recognising it, they would experience the indispensable prerequisites of art, which are tenacity and constancy.

For this reason, cooking is art. Of course, and luckily, it is far more sophisticated today than it was in the past, but the idea behind it and the food preparations are still essential parts of the process. A work of art is the result of a creative process that aims to stimulate knowledge paths. In the cooking process, in particular, where preparation can be separated hardly from its result, the dish served at a table is representative of something other than itself and to which we would not want to add or take away anything if prepared, as we say, artfully.

Like all arts, the cuisine also has its inflexible judge: time. Actually, like music, art moves through time, following its beats and pauses. “Prepare this, and while you wait, prepare something else.” And of course, the doses, with some unexpected and brilliant touches like those coming from Mozart’s music for clarinet. A small mismatch in orchestrating a plate and everything goes up in smoke so that we could say that the art of cooking is nothing but the art of balance and waiting.

Notoriously, we know that cooking is also a poetry. However, the poetry of an iron metre such as the Dantesque tercet. It is only from the greatest and most stringent rigour that, as we can see, the most imaginative and delicious recipes are born. All this because of a mental mechanism that sees a person who, forced to proceed along a narrow and well-defined path, find routes that would be unthinkable in a state of full freedom of movement.

Cooking is then a little like life where nothing can be left to chance. Living to the fullest is nothing more than respecting one’s own limits and at the same time being able to give one’s best with the ingredients available.

It is an intriguing metaphor if we think of the quantity and variety of food available in the most luxurious kitchens and the food shortage of the poorest regions of the world.

However, even if some of the above-mentioned ancient parents of ours knew, not effortlessly and even at the risk of their own lives, how to put together lunch and dinner, we can conclude that food and cooking certainly have hidden ties with all the arts. More than anything else, they are an extraordinary vehicle of unity and sharing, which are natural human feelings. And if the food we share is tasty and well prepared, it gets even better.

Some food is good for our health, and some harmful to us. The production of healthy food decreases and almost eliminates the impact on available resources and eliminates most of...

by Franco Banchi Not everyone knows that UNESCO in 2011 declared the 30th of April the International Jazz Day to celebrate such a renowned musical genre and its ability to unite...