MARSILIO FICINO: food and therapeutic optimism

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food....

Filter by Category

Filter by Author

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food....

Posted by Franco Banchi

At the port of Livorno, no one had noticed the rustling of that bulky cloak. Blessed by the most desiring stars, the curved shape of Settimontano Squilla was embarking on a...

Posted by Franco Banchi

The rigorous and meticulous Immanuel Kant, the milestone of modern philosophy, pleasure and pain of high school students, also had its own detailed “gastronomic...

Posted by Franco Banchi

To talk about Florentine festivals, with particular reference to the Renaissance, means to look in-depth at the very fabric of the “City of the lily”, in all its sides...

Posted by Franco Banchi

Time machine does not always proceed backwards towards extraordinary and memorable days. Actually, 1 December 1928 appears as an ordinary working day. Yet, behind the crumpled and...

Posted by Franco Banchi

The adventure of our magazine starts with young people and a mission announced as quite dangerous. On an almost spring morning, we have had a long conversation with the girls and...

Posted by Franco Banchi

CLIMBING THE SKY IN HEALTH

The great humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino, whose Academy ennobled Florentine culture in the Laurentian era, had a special relationship with food. To be more rigorous, he connected food’s essential vital factor with that entire “macrocosm” that connects every earthly man (the microcosm) with the sky.

The statements we find in many of his works are emblematic. Among these, the following, which incorporates Diogenes Laertius: “Phoebus gave birth to Asclepius and Plato for mankind: the former to take care of the body, the latter to take care of the soul”.

At the centre of this theory is Ficino’s therapeutic optimism, already suggested by Thomas of Brabant. Colours, sounds, metals, precious stones, herbs, beverages, and much more are our allies to combine the physical and spiritual world, earth and sky.

If we carefully read the notes the great neo-Platonic thinker unfolds in his writings, we find a widespread insistence on the opportunity given to the wise, certainly not to the illiterate, to “climb” the sky in health, both physically and spiritually. He often speaks of the importance of the admincula, thanks to which the body becomes stronger drawing on the “quintessence” (a celestial source of generation and growth) present in various substances: gold, precious stones, perfumes, balms, aromatic herbs, etc.

With these ideas, Ficino explicitly expresses his Platonic adherence. Putting the banquet at the basis of the general philosophical education, he compared the initiation towards what we love to the progressive ascension on a staircase (Symposium, 210 A-212 A).

FOODS OF HEALTH AND HARMONY

Ficino dedicates monographic texts to the complex world of food and what revolves around it. Among these, we should mention a book, which already from its title, both elaborate and highly descriptive, makes its intentions very clear: De sufficientia, fine, forma, materia, modo, condimento, auctoritate convivii, written in 1476.

Several times, in this and other works, he speaks of foods in tune with cosmological philosophy. Pure wine, sugar. White, thin, and bright substances or precious foods to choose according to harmony or chromatic co-optation, such as egg yolk and saffron (as they evoke the sun by colour, light, and symbolism).

In particular, Ficino is very careful with the virtues and vices of wine. Always accompanied by a small flask of wine from the Valdarno hills, close to his hometown Figline, he is very strict on the matter. He recommends drinking only “good, pure and aromatic” wine and avoiding “musts and murky wines”, which are very harmful to the body’s balance. Equally severe in describing the relationship between eating and drinking, the philosopher advises, “To eat and drink less than one usually does”, although, he adds, “one should eat more than what one drinks”.

Ficino is generous with advice on food and, at times, he discusses the cooking process, too.

An example concerns meat, which must be “dry”. Here is what he writes: “If you use stewed meats, put them to roast, but pierce them well inside filling them with sour seasonings, some pepper or cinnamon, coriander, and salt”.

The fear of foods, in which prevail negative humour, harmful to health, is constant, so much so that he firmly states, “Danger is in the heat together with the damp and putrefaction”.

Consequently, he recommends, among other things, to avoid mushrooms, wet herbs, purslane, and pumpkins. Among moist food, he mentions lettuce (with a splash of mint, cinnamon, and very fine clove basil), blue sow thistles (Cicerbita), and greater burnet-saxifrage (Pimpinella Major).

Also singular is the indication that fruit is too hot/moist, soft or tender. For example, if you eat watermelon or “fat” plums, you should afterwards balance such excess eating fennel or sweet orange juice with salt, combined with some healthy and dry wine.

The digression on fish is similarly very interesting, always conditioned by the idea of balancing and mitigating what is cold and wet, harbinger, if in excess, of “all putrefaction”. According to Ficino, it is, therefore, necessary to flee much fish except the small river ones (from stony environments, with clear and running water). They are delicious covered in flour and fried in oil, accompanied with verjuice or vinegar sauce; or seasoned with sweet oranges, salt, pepper and cinnamon.

He could not avoid clear reasoning on fruit, showing some scepticism on its healthiness, apart from almonds and hazelnuts, pears, peaches, loquats, cornel berries, dry plums and pomegranates.

THE PLAGUE: TIPS AT THE TABLE AND THEREABOUTS.

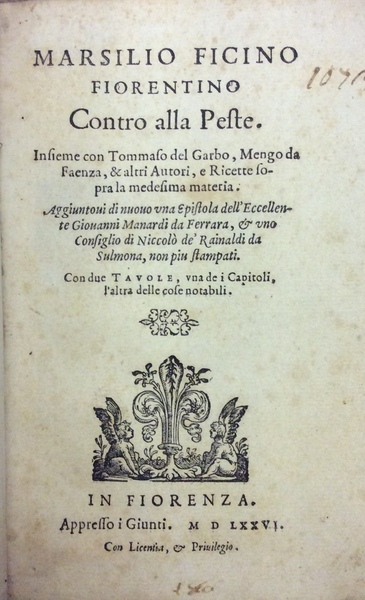

The neo-Platonic philosopher, however, delves into another topic that is actual even today. With specific reference to the cyclic plague epidemics affecting Tuscany, he wrote Consiglio contro la pestilenza (Advice against the plague), in 1481.

Even in this case, the initial comparison Ficino develops between earth and sky as complementary dimensions of the material and spiritual health is interesting: “The nature of these earthly gods is made up of a composition of herbs, stones, aromas, all of which possess in themselves an innate divine virtue”.

In other passages, he introduces a new evocative combination: “Nature and love are the real and true magicians”. He compares the magician to the farmer, who, through the combination of seeds, makes the land prosper. It is the apology of the thaumaturgical function of the Renaissance philosopher, a physician of both body and soul.

In this regard, Ficino does not exempt himself from listing the foods that “must be used” in that critical time. Just to give a hint: dry, tasty, sour, acidic foods, avoiding broth and fat; greasy and gummy desserts. He continues, “Drink simple or somewhat genuine, non-sweet wines (…) also watered down with very light and clear water.

Then, he talks about useful spices to use in food preparation, with an eye not just linked to taste: red sandalwood, fine cinnamon, red and white carnations, white and red corals, cardamom, roses, spodium, etc.

It is a treasure chest of wonders. An authentic panacea that protects us against all evil.

There is even a piece of amazing advice he gives to people with digestive problems. It is a therapy entrusted to the precursors of pills, “big in the shape of chickpeas”, in which aloe, myrrh, and saffron are concentrated and purified, so to speak, with eau de vie in winter and sorrel syrup, cedar or lemon in summer.

You can breathe a lot of Eastern air in these Ficinian suggestions. Moreover, it is all too natural to think of the cavalcade of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli as the theatrical backdrop of this great show of food and beverages, smells and flavours, exotic pharmacopoeia, assorted stones and lights. Right there, our Marsilio da Figline appears lost among the many, but very distinguishable. To each his cameo.

FRANCO BANCHI

Biography of Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (Figline Valdarno 1433 – Florence 1499), philosopher and theologian, was the greatest exponent of Italian Platonism of the 15th century. He studied in Florence where Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned him the translation of Plato’s works. He also translated the Corpus Hermeticum and the Enneads by Plotinus. He gathered around him a circle of friends and disciples, which took the name of Platonic Academy, the “new Athens”.

Among his works, emerge the Platonic Theology (1469-74), De Christiana religione – On Christian Religion (1473), De Vita – On Life (1489) and the Epistles in 12 books. Through the Platonic doctrine, Marsilio Ficino sees the human microcosm as the true centre of the universe. Men have a privileged status, thanks to their contemplative, cognitive, but also creative ability. Linked to the doctrine of the mind-soul is that of love, seen as the unifying and thaumaturgical principle of reality, as a “cosmic knot”. Marsilio Ficino’s work had extraordinary importance in the history of thought: for several centuries, the learned Europeans studied Plato and the Neo-Platonists usually through Ficinian translations and comments. However, those texts also had value inside the Florentine context: Ficino’s works inspired the elegant environment of the Medici family. Many works, such as the Stanze by Poliziano and the Primavera by Botticelli, ideally embody Marsilio Ficino’s philosophy.

by Franco Banchi New Atlantis is an unfinished utopian novel by Francis Bacon, written in 1624 and posthumously published in 1627. Bacon tells the story of a group of 51...

Since the dawn of time, man has tried to get in touch with the gods, perceived as superior intelligence, through the modified states of consciousness, both with the help of...